Why the built environment doesn't belong on a blockchain.

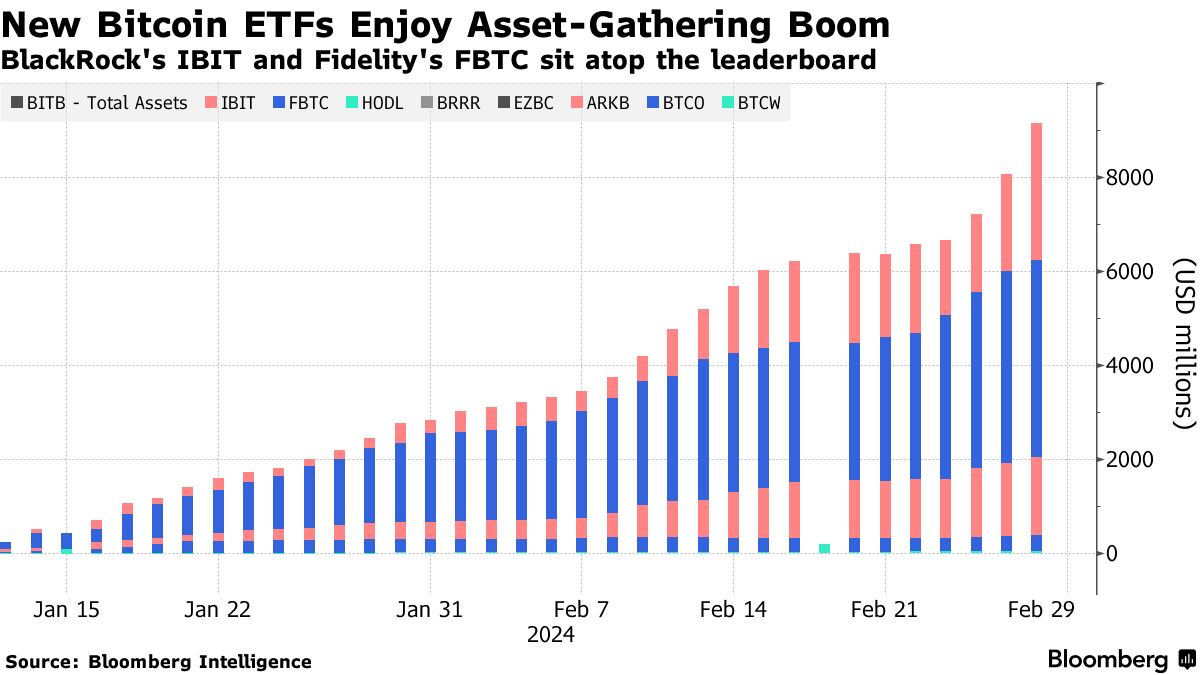

With the approval of new exchange-traded funds (ETFs) in the US, Bitcoin is back in the spotlight. Narratives which ride on Bitcoin's coattails are also returning and competing for engagement. As newer entries in the crypto lexicon, NFTs and Web 3 might seem familiar as they resurface. Older themes around applying blockchain technology and tokenisation are also coming full circle. These ideas have been tipped to transform sectors like real estate for years. Despite the renewed hype around tokenising assets, there's a case to be made that buildings will never belong on a blockchain. Is there really any practical overlap between a decentralised ledger system and physical assets in our built environment?

This post is a reminder of the problems that Bitcoin addresses and the unique trade-offs with its blockchain. It also explores the role of land registries in assuring integrity and trust in real estate markets. Bitcoin and real estate both rely on transactional ledgers, but these have fundamentally different characteristics.

Blockchain technology and tokenisation.

In recent interviews about the new Bitcoin ETFs, high-profile figures in finance like Larry Fink and Jamie Dimon both brought the discussion around to tokenisation.

Larry Fink on the iShares Bitcoin ETF, January 2024

"we believe the next step going forward will be the tokenisation of financial assets"

Larry Fink, January 2024

Dimon remains dismissive of Bitcoin, but raises the merits of blockchain technology for tokenising financial assets like real estate:

"Blockchain is real, it's a technology. We use it, it's going to move money, it's going to move data... Think of a cryptocurrency with an embedded smart contract in it, then we can use it to buy and sell real estate, and move data, that may have value. Tokenising things that you do something with. Then there's one which does nothing, I call it the pet-rock, the Bitcoin or something like that..."

Jamie Dimon, January 2024

Tokenisation promises to convert financial assets into digital tokens which are recorded and traded on a blockchain. Each token represents fractional ownership of an underlying asset. With real estate, this would mean mapping land or buildings in the built environment onto a blockchain. The intention is to improve access to markets, boost liquidity, and improve transparency in investing. Tokenisation is said to reduce costs whilst improving the efficiency and speed of processes in a market. If a blockchain sounds like the right tool for the job, it's worth revisiting Bitcoin first.

Bitcoin blockchain basics.

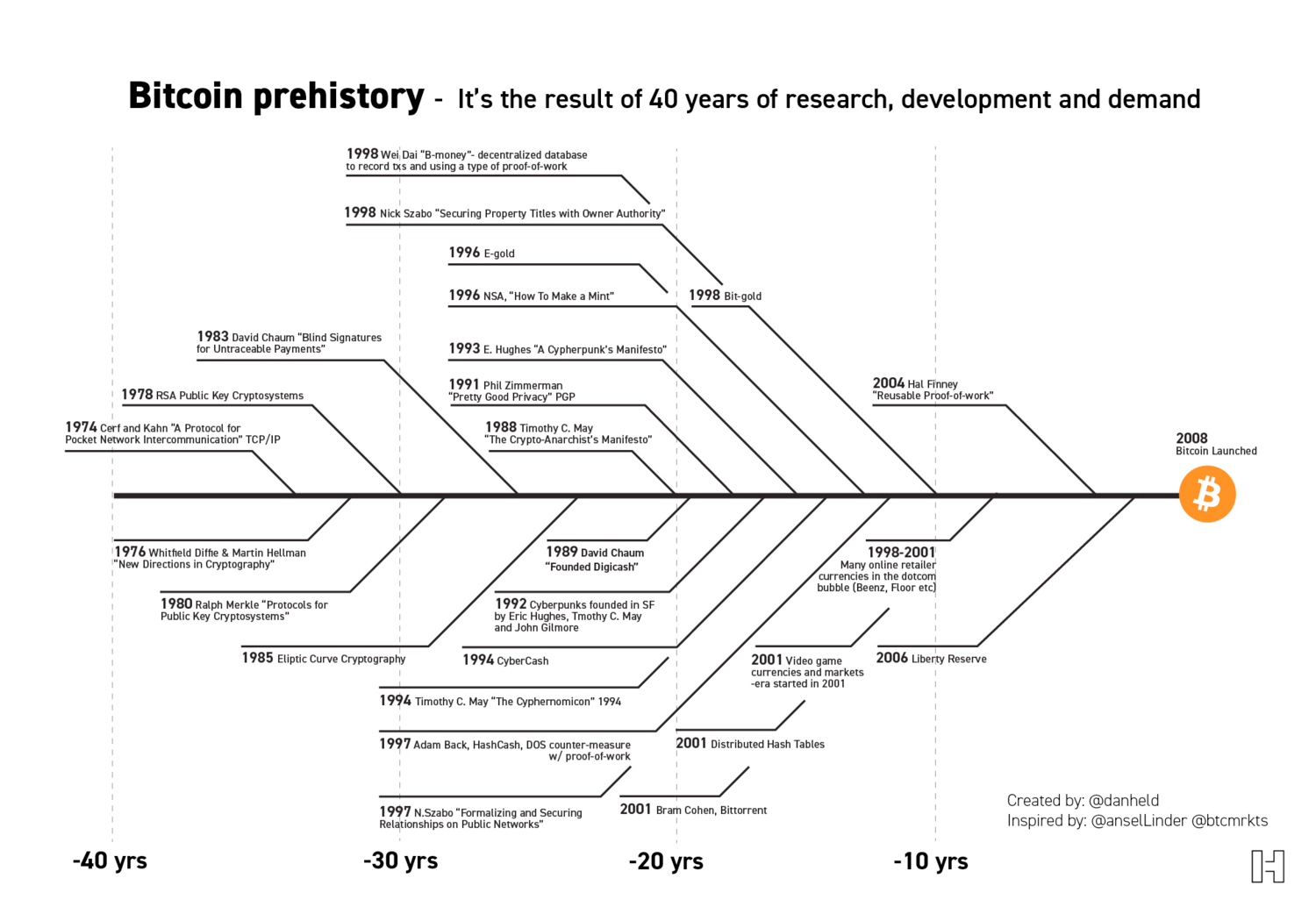

Even after 15 years, the problems that Bitcoin addresses and its key trade-offs are still underappreciated. Based on their media appearances, Fink and Dimon have some homework left to do. Before applying blockchain technology to other assets, they're overdue an interview covering some Bitcoin fundamentals. Cedric Price's famous provocation, "Technology is the answer, but what was the question?" couldn't be more relevant when appraising a blockchain from first principles. Doing so prompts us to ask why Bitcoin exists and what problems it was created to solve. It's also worth considering its limitations. What are the trade-offs that come with its unique design, and how do they impact its effectiveness and wider application?

"Technology is the answer, but what was the question?"

Cedric Price, 1966

Bitcoin was created to enable peer-to-peer transactions online without the need for trusted third parties like banks. With its fixed and programmatic supply schedule, it also solves the problem of unexpected inflation. At first, Bitcoin can sound rather abstract or academic, but the monetary issues it addresses are increasingly perceptible. Dependence on trusted third parties is becoming a glaring weakness of modern currencies. Banks may seem neutral and benign until transactions are blocked or accounts are closed. As digital payments take over from physical cash, currencies as we know them become especially vulnerable to censorship and seizure.

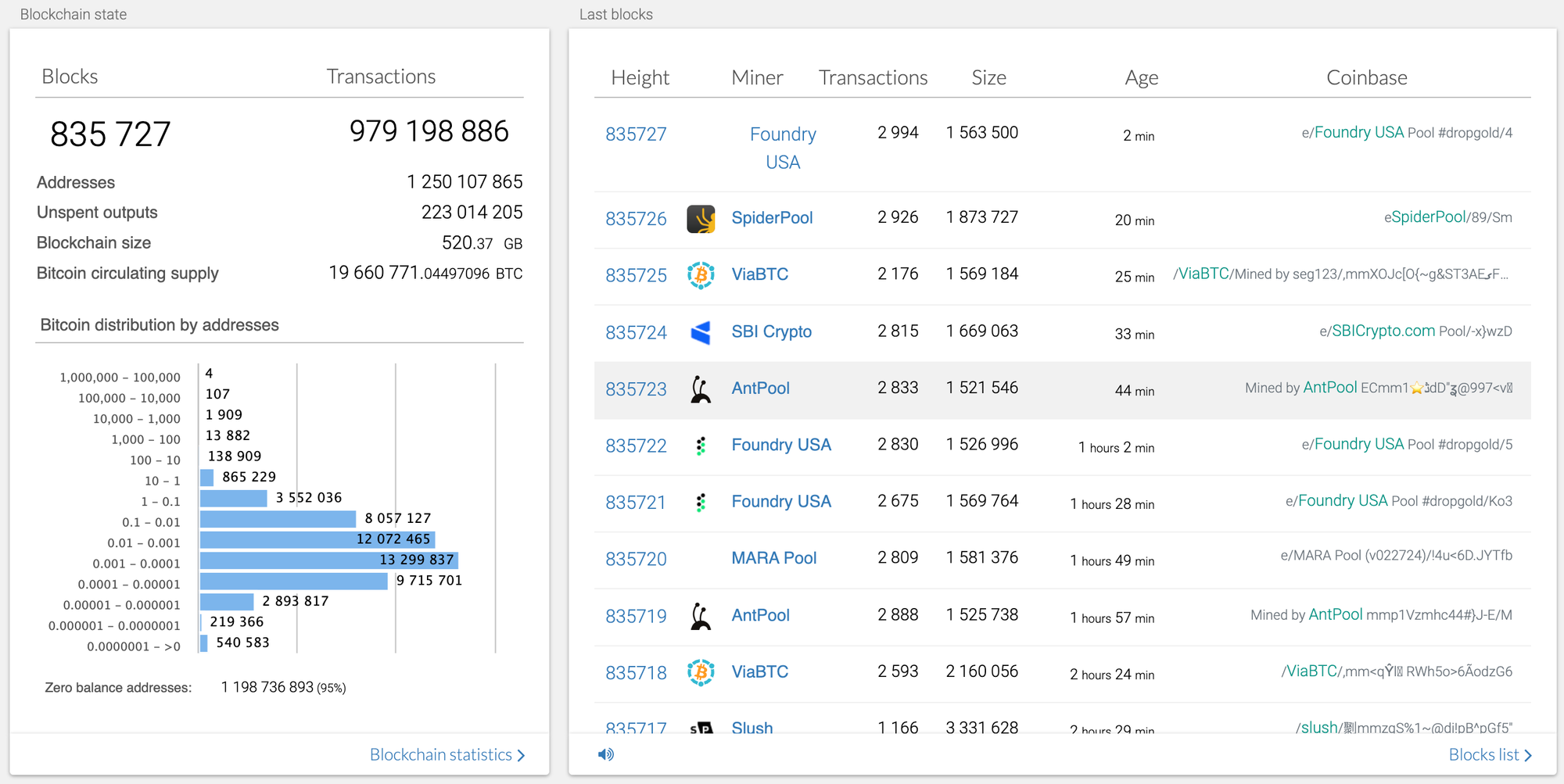

Bitcoin's decentralisation ensures that efforts to censor or halt transactions are ineffective. Every user follows the same protocol rules and no single authority controls the network. Once a user initiates a valid transaction and it gets recorded in the blockchain, it becomes irreversible. This permanence can be independently verified in real-time using a block explorer, where anyone can check balances and transaction histories. Users who manage their cryptographic keys effectively become their own bank, safeguarding their bitcoins from unauthorised access or seizure.

Alongside the risks of censorship and seizure, the creator of Bitcoin was acutely aware of the problem of inflation. When the control of a transactional ledger lies with a central authority, users must trust that the number of units in the system won't be interfered with.

"The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that's required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust."

Satoshi Nakamoto, creator of Bitcoin

Bitcoin solves the problem of unexpected inflation as the total number of units is limited. Their issuance is fixed in time and completely programmatic. A supply cap of 21 million bitcoins is enforced on a completely decentralised basis; a new constant in the economic landscape. With his provocation in mind, Cedric Price may have been a fan. As an emerging technology, Bitcoin answers some very tough and relevant questions. With its censorship resistance and transparent, fixed supply, the protocol is uniquely differentiated from any other transactional ledger. It's an impressive achievement based on decades of work, but it's important to acknowledge its limitations.

Bitcoin's critical tradeoffs.

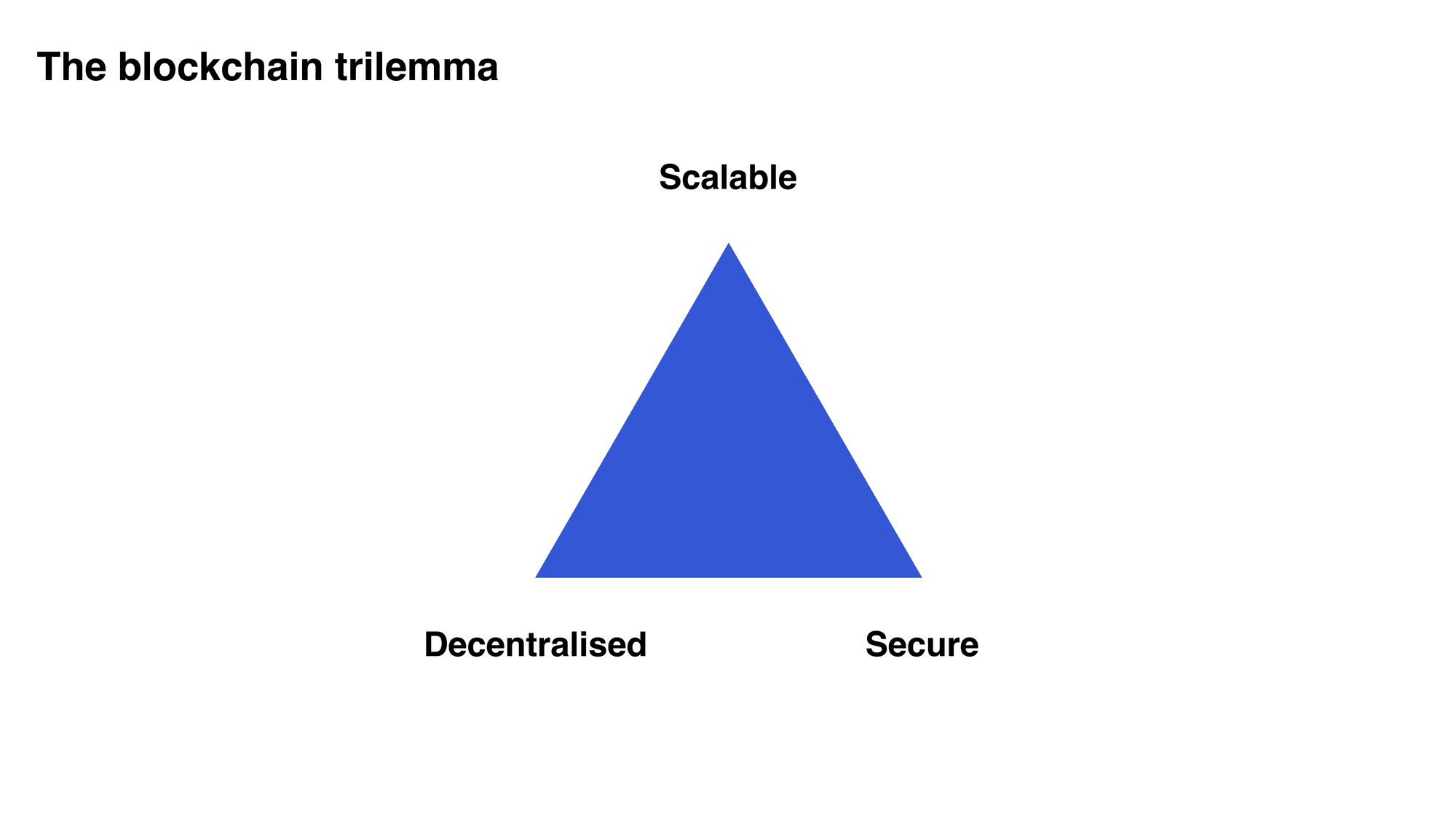

Bitcoin enables digital transactions without a trusted third party and solves the problem of inflation, but, like most technologies, it does have trade-offs. To appreciate them, consider a trilemma, a situation where you can only optimise two out of three factors. This concept isn't unique to a blockchain. With a building project, there's a well-known trilemma involving the balance of quality, time, and cost. Good luck achieving a high-quality build on schedule unless you have very deep pockets.

With a blockchain, we encounter a trilemma including scalability, decentralisation and security. While the Bitcoin protocol opts for decentralisation and security, it does so at the expense of scalability. At a high level, this is achieved by limiting transaction throughput and using an energy-intensive consensus mechanism (proof-of-work). These characteristics might seem counterproductive at first, but the design is completely intentional.

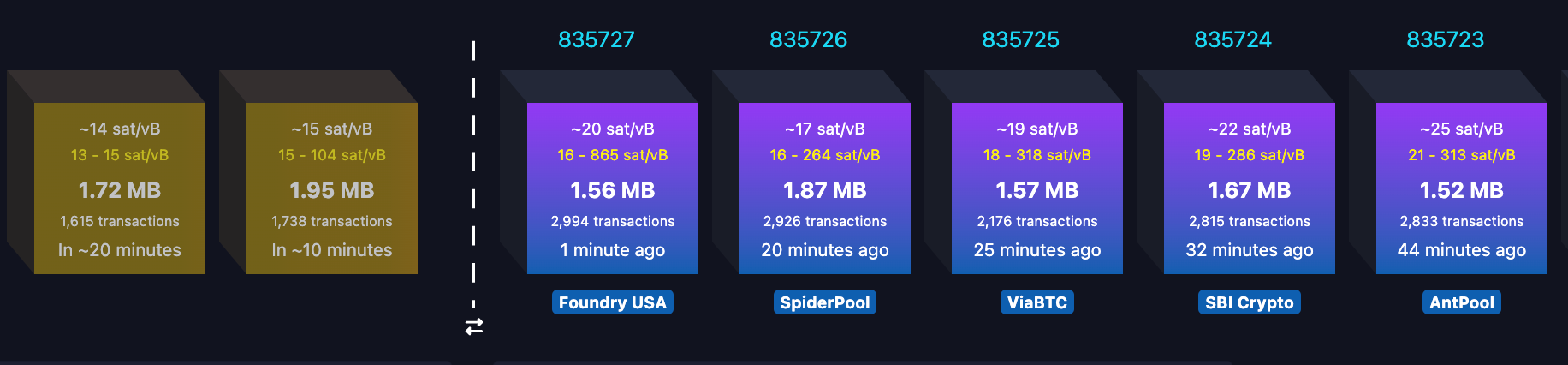

As an interconnected system, aspects of Bitcoin are notoriously difficult to distil. However, the tradeoff between scalability and decentralisation can be illustrative without delving into energy use and security. Blockchain scalability centres on throughput; how much data can be included in each block (block size), and how often new blocks are recorded in the chain (block time).

Bitcoin's block size is relatively low, typically below 2 megabytes in recent months. With only megabytes to play with, each block is limited to a few thousand transactions. Combined with an average block time of 10 minutes, this results in a sluggish throughput of just 5-7 transactions per second. Layering technologies like lightning can scale Bitcoin beyond this, but the blockchain itself is very limited indeed. The Visa network is by no means a like-for-like comparison, but its throughput of 65,000 transactions per second puts things in perspective.

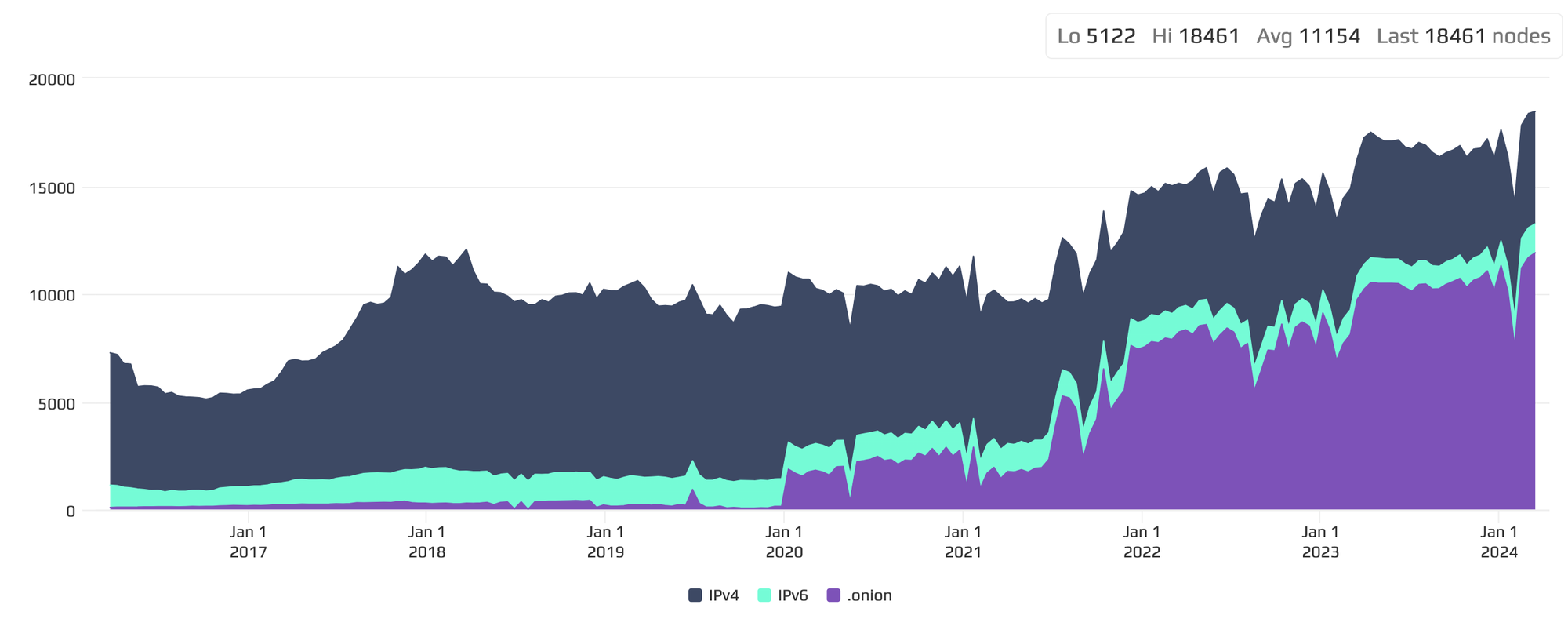

To appreciate how throughout links to decentralisation, consider some of the hardware that makes up the Bitcoin network. Computers which run the Bitcoin software are called nodes. These are pivotal as they independently enforce the rules of the Bitcoin protocol. Seeing as Bitcoin is free and open-source software, anyone can download it and begin validating transactions and blocks. Bitcoin's small blocks and slow block time ensure that operating a node is very economical. As low-end computers and domestic internet connections can handle the blockchain, the number of nodes validating the system is maximised. Many nodes are run by individuals using basic hardware that costs £100-£400. This accessibility is crucial, the more users who participate by running a node, the more resilient and decentralised the system becomes.

If the system prioritised scalability with a high transaction throughput, the hardware and network requirements to run a node would become much more onerous. If throughput were doubled, so would the disk space and bandwidth required. When a blockchain network comprises fewer nodes, the enforcement of the protocol becomes less decentralised. In this scenario, it would be easier for a small number of parties to collude and attempt to change the rules. A handful of central banks working together to manipulate the supply of currency in the global economy is a useful parallel. Decentralisation exists on a spectrum, but Bitcoin stands out from any other network with its tens of thousands of independent nodes. Fifteen years of data in the Bitcoin blockchain is only around 600 gigabytes, and this is distributed across every node in the network. What the system lacks in speed, it makes up for in immutability and the way that it credibly enforces the protocol.

In addition to being slow, Bitcoin is notoriously energy-intensive, but these factors aren't bugs or failings. Rather, they are design choices which differentiate its blockchain from other transactional ledgers. Critics aren't pausing to consider the questions which Satoshi Nakamoto might have grappled with; perhaps "How can we ensure the integrity of a transactional ledger without relying on a trusted third party or central authority?". From this kind of question, we can appreciate why speed and efficiency aren't prioritised in the solution. Despite its tradeoffs, the Bitcoin network is processing irreversible transactions with over 1 trillion dollars in value each month. It's also enforcing the fixed supply of 21 million bitcoins; all autonomously and without the need for a central authority to keep score.

Revisiting tokenisation with Bitcoin's trade-offs in mind, what would the benefits of a blockchain be in real estate? Would it make sense to limit the throughput of a new ledger system to improve its decentralisation? Is it important for participants in real estate markets to be able to transact without the involvement of third parties or centralised authorities?

"Technology is the answer, but what was the question?"

Cedric Price, 1966

Centralisation and trust in real estate markets.

Considering Bitcoin's core principles of decentralisation and minimising trust, the idea of tokenising legacy financial assets on a blockchain starts to seem a little contrived. A closer look at transactional ledgers in real estate is a helpful reference to appraise if a blockchain can be a general-purpose technology. Perhaps a ledger system that's validated by a decentralised network has a narrower use case than Fink and Dimon realise.

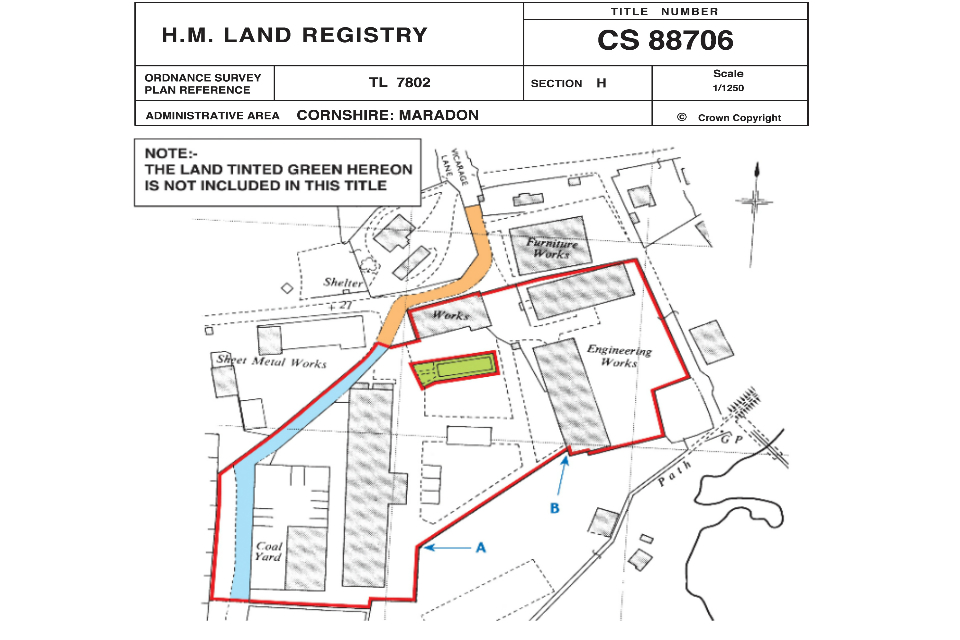

Land and buildings in our built environment are familiar examples of tangible assets in the world of finance. Although physical, real estate assets are recorded on digital ledgers and databases. In England and Wales, His Majesty's Land Registry (HM Land Registry) registers the ownership of most property. When it was formed in 1861, it relied on paper title deeds to show the chain of ownership for each property. Today, records are digital, and anyone can search for information via a government portal. Further to recording ownership, the HM Land Registry helps to underpin the real estate market in England and Wales by offering a state-backed guarantee on property titles. This gives buyers and sellers assurance and legal protection. Land registries play a key role in enforcing property rights in the built environment, they are trusted to record an authoritative history of changes in ownership.

For real estate transactions in the UK, HM Land Registry is a clear example of a central authority. Its presence is a reminder of how strongly the market contrasts with the decentralised and peer-to-peer nature of the Bitcoin network. Real estate can be owned in various ways; directly by an individual or company, indirectly through shares in a real estate investment trust (REIT), or perhaps in a novel fashion involving tokenisation and a blockchain. Still, at the base level, the market functions by trusting a central authority to record changes in ownership. Transactions may be made between two parties, but they're always downstream from the land registry. When property rights are enforced by government entities, it's centralisation which provides trust in the market and allows assets to reliably change hands. With this in mind, applying a decentralised blockchain which is slower and more energy-intensive than a conventional database doesn't appear to solve any problems for participants in the market.

"Stated simply, if centralization is a requirement of the design, a database is a much less costly solution — in terms of economics and energy usage."

Jeff Booth, Finding Signal In A Noisy World

Imagine BlackRock tokenised a building in their UK real estate portfolio so that investors could trade fractional shares on a blockchain. The building would still relate to a title number on HM Land Registry. The title deed would still show the date that the freehold for the property was transferred from the previous owner to BlackRock. The degree of decentralisation with an adjacent BlackRock blockchain would be of no significance. Ultimately the property would still exist as a ledger entry in an inherently centralised system. In stark contrast, Bitcoin users transact in a closed system, completely independent from any government entity. Energy intensity and low throughput are worth it for users if they can transact freely and verify the system independently. Unlike in a real estate market, the degree of decentralisation in Bitcoin is paramount, this ensures censorship resistance and enforces the protocol and its fixed supply.

Just like the previous example involving banks, trusting a central authority is all well and good under favourable and uncontested circumstances. Would ownership of property tokens on a blockchain be beneficial if the possession of a building became disputed?

With real estate in the built environment, possession is never absolute as it relies on how property rights are enforced. This is highlighted by compulsory purchase orders (AKA eminent domain). Just as a land registry grants title to property, it can also take it away. If a government decides that a piece of privately owned land is needed for public purposes such as building new rail infrastructure, they have the power to seize it. In this situation, owners of property tokens on a blockchain would be in the same boat as local homeowners or businesses with conventional ownership of their buildings. Whether ownership is direct or indirect, consent or willingness to sell would be irrelevant; the government can enforce a transaction at a rate they deem appropriate. In the Bitcoin network, possession relies on cryptographic keys rather than conventional property rights. If these keys are kept secret or lost, there's no way for a government to force a transaction. Everyone in the Bitcoin network follows the rules of the protocol, however rich or powerful they may be.

Tokenising the built environment on a blockchain presents a mismatch of fundamental principles and practicalities. When transactions and ownership are enforced by central authorities and property rights, a traditional database still seems like the right tool for the job.

Can centralisation and decentralisation mix?

Tokenising real estate on a blockchain is claimed to have several benefits for the real estate sector. These centre on improving efficiency, reducing costs and boosting accessibility and transparency in markets. Anyone who has gone through the process of buying or selling a property in the UK can appreciate that the process has room for improvement. Even though the UK is one of the most trusted and valuable real estate markets in the world, transactions remain slow, expensive, and parts of the process can seem archaic and opaque. There's certainly scope for technology to streamline transactions, but blockchains which minimise trust and increase decentralisation are a distraction. Returning to the blockchain trilemma, it's not worth compromising on security or scalability when decentralisation is unnecessary. When the integrity of central authorities and property rights gives market participants trust, the security, speed and interoperability of conventional transactional ledgers are a more productive focus for entrepreneurs.

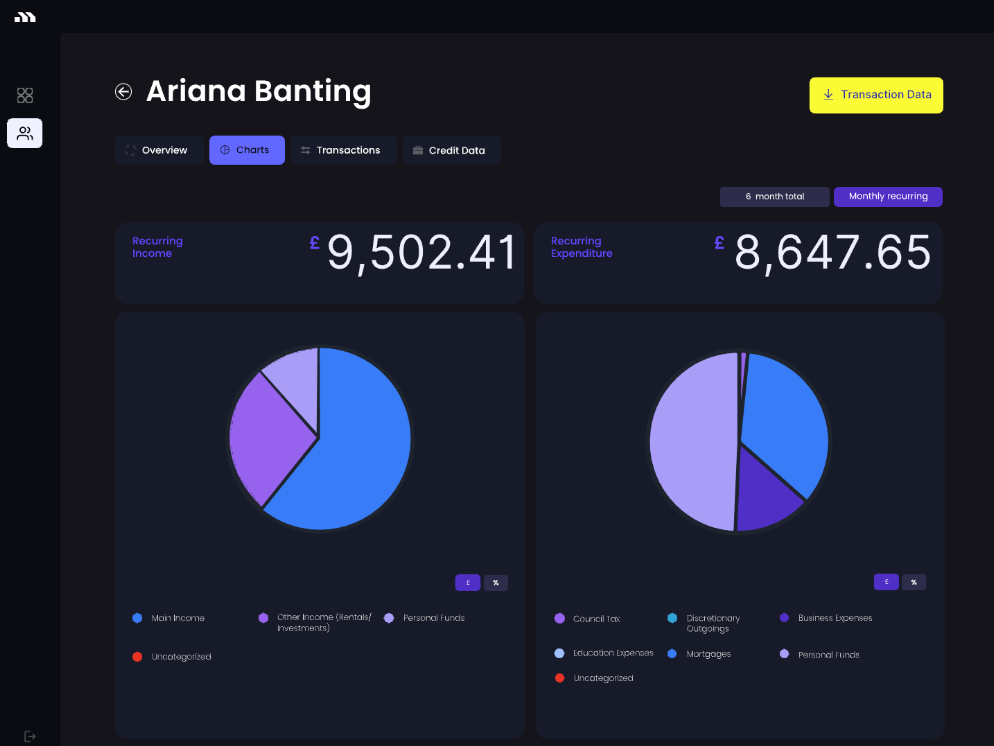

In today's global real estate market, jurisdictions with dependable land registries and well-defined property rights are the most sought-after. Capital flows to regions characterised by political and economic stability. In future, the most attractive markets will have stability, integrity and trust from central authorities, alongside the most seamless and streamlined transaction processes. Processes will be improved by automation and better interoperability between the systems used by stakeholders. This could involve interactions between buyers and mortgage brokers, sellers and solicitors, or solicitors and central authorities like HM Land Registry. In the UK, prop-tech startups like MortgageBloc exemplify the opportunity for improving interoperability. By integrating open banking APIs, MortgageBloc lowers friction and accelerates the mortgage underwriting process. No blockchain necessary.

Circling back to Bitcoin, the new ETFs represent a novel and less direct way for users to own the asset. Companies like BlackRock are selling them as a more convenient approach, customers can trust their brokerage account rather than their technical know-how. Record demand for the ETF products suggests a strong product market fit. Just like other ETFs, this convenience only applies to citizens in developed countries who have access to regulated banking and investment accounts. That said, possession of bitcoin directly on the blockchain is still accessible to anyone with a smartphone, an internet connection and the curiosity to learn. Because the Bitcoin blockchain remains decentralised, censorship-resistant and accessible at the base layer, the ETFs augment the network whilst respecting its DNA. With applying blockchain tokenisation to real estate, the opposite is true. Adding a decentralised approach to indirect ownership doesn't complement or augment the base layer, it simply clashes with it.

Closing thoughts.

By revisiting Bitcoin, we've established that it addresses important problems which are unique to money. Its blockchain is relatively slow, limited in throughput and resource-intensive. However, the tradeoffs in its design ensure a high degree of decentralisation and that the rules of the system are credibly enforced. Energy use and security are well worth studying more closely. Bitcoin transactions are digital and circulate in a closed system. Users can independently verify the total supply and audit the blockchain in real time. Possession is absolute as it's enforced by cryptographic keys and a decentralised protocol rather than property rights.

In the built environment, real estate transactions rely on the credibility and integrity of central authorities like HM Land Registry. Participants in the market are exchanging tangible assets, but trust third parties to maintain an accurate snapshot of ownership in a digital database. Land registries are often digital and publicly available, but users cannot independently verify information. Possession of land or buildings can take various forms, but it's never absolute. Ownership is contingent on how property rights are enforced as exemplified by situations with compulsory purchase orders.

Whilst the idea of tokenising real estate on a blockchain is said to have several benefits, proponents are overlooking important first principles. These extend from the trade-offs with a successful blockchain to the inherently centralised nature of real estate markets. In order to streamline the processes in real estate transactions, prop-tech startups will find better product-market fit by improving existing transactional ledgers and their interoperability. The more closely we study Bitcoin as a unique monetary innovation, the clearer the case gets that the built environment doesn't belong on a blockchain. If tokenised real estate is the answer, what was the question?

References