Cheap money; expensive, empty houses.

In the UK, the perpetual state of crisis in the housing market is a popular talking point. There's an acute shortage of decent, affordable housing. Coverage of government policies, demographics and the mismatch between supply and demand comes our way with a regular cadence. Money-wise, foreign investment and low-interest rate policies sometimes come up, but these themes only scratch the surface of a deeper and less explored dynamic. Seeing as our currency makes up one half of every property transaction, one would think that its characteristics would get more attention. The nature of our money fundamentally influences incentives within the housing market. If stakeholders want real debate or any meaningful change, its influence should be front and centre. Adjusting policies and rehashing old approaches has proven futile in alleviating the crisis. Perhaps it's time for a fresh perspective. This article aims to bring the properties of our currency into the spotlight, and expands on how its limitations lie at the heart of the housing crisis.

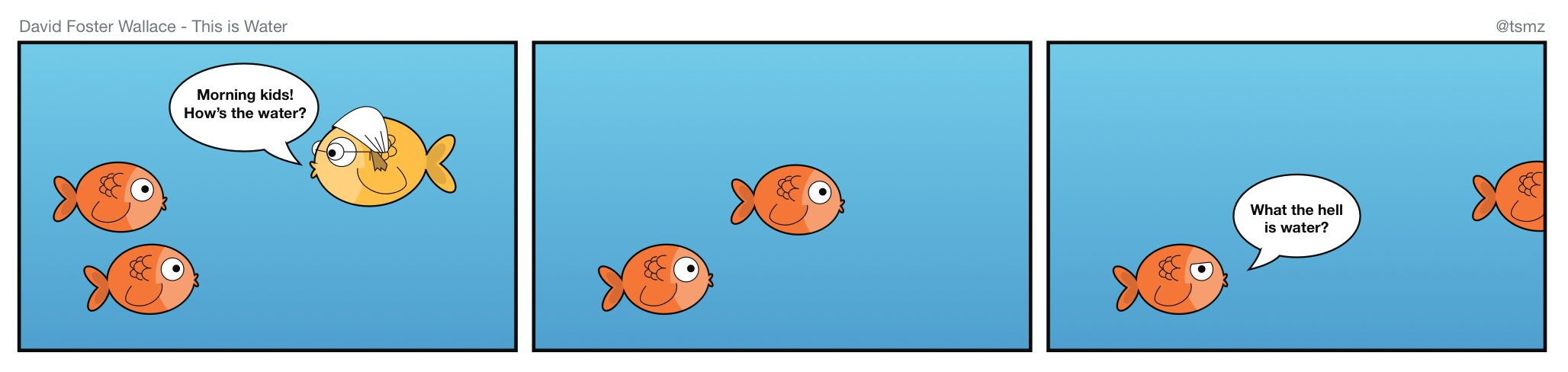

What the hell is money?

To appreciate how the pound influences incentives in the housing market, it's important to first understand the functions of money, and the properties which make a good form of money. Brits are conditioned to think of house prices in pounds, but the pound is only one manifestation of money. Not all monies are created equal. Also, the terms currency and money are often used interchangeably, but it's possible to have a currency that doesn’t satisfy the functions of money, and vice versa. With the current cost of living crisis, money is taking up more mindshare, but nuances aren't often discussed.

People have their own ideas and instincts about money, but just like with politics and religion, they don’t necessarily bring them up over dinner. It’s usually taboo, or a little bit vulgar if the conversation gets too personal. Nonetheless, in the abstract, things can get interesting very quickly. Especially these days. With the information age taking hold, our relationship with money is in a state of flux. Some principles will always stay the same; consider that money is highly desirable, but doesn't have any value in itself. Quite the paradox. Money is only ever valuable because of its ability to be exchanged for goods or services in the future, it enables indirect trade. A £10 note isn't much use at dinner time, rather the food it can buy (albeit less food than ever).

Regardless of your opinion on Bitcoin, its arrival has brought the question of “What is money?” into vogue. If you've relied on the BBC news over the last 10 years, you might have missed this important question for fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD) centring on illicit activity or Bitcoin’s environmental impact. Outside of the mainstream media, however, you may have come across the initiated uncovering the history and theory of money in some thought-provoking books, articles and podcasts. Unlike our pounds, Bitcoins are not “backed” by anything, but posses excellent monetary properties. Bitcoin is slowly but surely satisfying the functions of money, or so the argument goes.

What are the functions and properties of money?

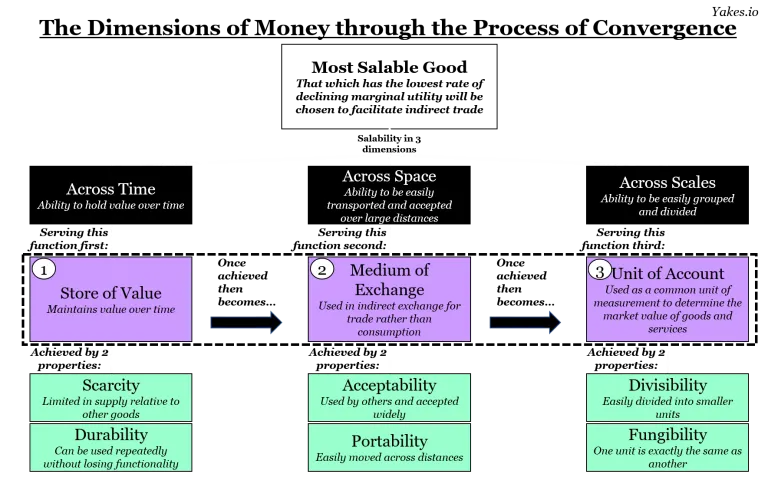

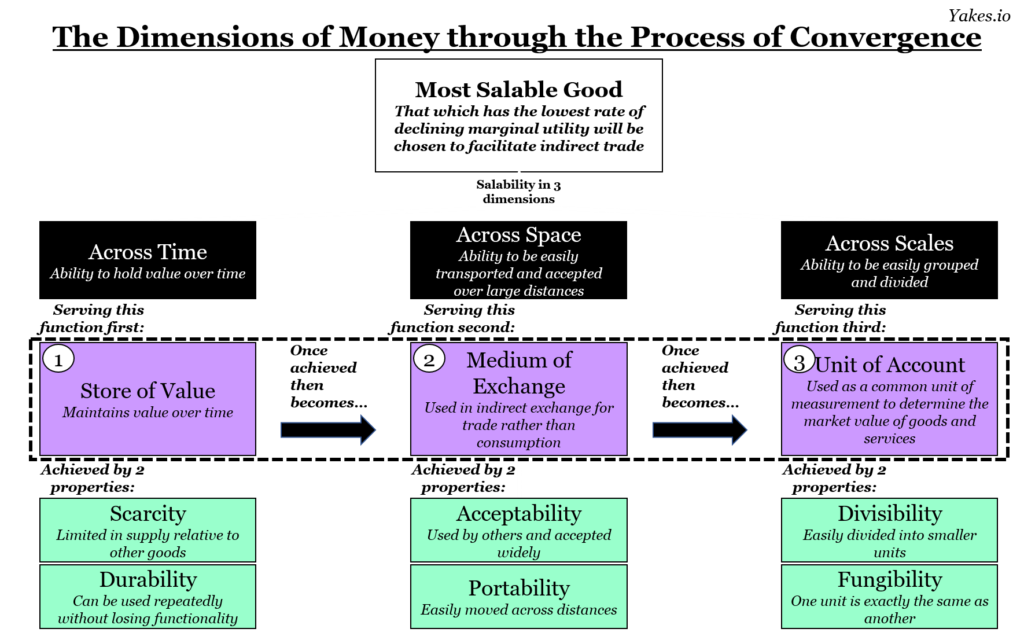

The three functions of money are as follows:

- Store of Value

- Medium of Exchange

- Unit of Account

Store of value is critical; money must withstand repeated use and hold its purchasing power in order to enable indirect trade, whether it's later today, next Tuesday or next year.

Durability and scarcity are key properties which support this function. Imagine trying to use pieces of fruit as money, you wouldn't get very far.

When it comes to medium of exchange; money must be easy to transport and be immediately recognised and desirable wherever it's taken.

Portability and acceptability are perhaps the most relevant properties which support this function. Monopoly money is portable and recognisable enough, but good luck exchanging it for goods or services outside the game board.

The unit of account function relates to measuring the value of goods and services. A good money has the properties of divisibility and fungibility when considering different scales.

Divisibility is arguably one of the primary failings of gold as money; it’s not so easy to subdivide for small-scale transactions. A gold sovereign coin is roughly the same size and weight as a modern one pound (£1) coin, but as of May 2023 is valued at around £400. Not much use at the corner shop.

Fungibility is a term usually associated with money itself and is equivalent to interchangeability. My £20 is the same as your £20 (unless you made a trip to Scotland recently).

How does the pound shape up as money?

At first glance, the pound checks off all of the properties introduced above. In terms of durability, banknotes have a prolonged circulation since the transition from paper to polymer in 2016. A digital bank balance never wears out. People working for fixed salaries or wages will tell you how scarce pounds can be, particularly given the prevailing cost of living crisis.

With the medium of exchange function, acceptability and portability have never been better. As long as you're happy to make card payments that is. With higher contactless payment limits, it's easy to tap and pay for day-to-day goods and services in person. Online checkouts are getting slicker too.

Perhaps with the exception of micropayments online, the pound seems perfectly divisible and fungible too. With cash used infrequently, there's less chance of ending up with a pesky Scottish £20 note.

Taking a closer look at scarcity, perceptions vary depending on your circumstances. For the Brits working pay-check to pay-check, pounds might not seem to go as far these days. The store of value function doesn't come into the picture if you're dipping into savings or tapping the credit card to cover everyday essentials.

"As the cost of living crisis drags on, almost a third of UK adults have dipped into their savings to make ends meet, collectively withdrawing more than £53 billion."

Bethany Garner, Forbes

Ask an asset manager and you'll get a different perspective. If you're in the business of building wealth for your clients, pounds can be hot potatoes. They need to be put to work to mitigate the impact of inflation. It's a lack of scarcity which drives long-term decision making. With an ever-inflating supply of pounds, the challenge becomes making smart acquisitions, investments and speculations which have the potential to grow. Putting money to work is not without risk, but when pounds don't store value into the future, sitting on too much cash is risky in itself. "Mo' money mo' problems."

No one knows exactly how many pounds there are today, let alone how many there will be 5 years from now. Regardless, it's clear that there are more sloshing around in the financial system than ever before. We used to talk about millions and billions, now we’re talking trillions. The supply of our currency is ever increasing, and its purchasing power is ever declining. The pound has never been cheaper as a form of money than it is today.

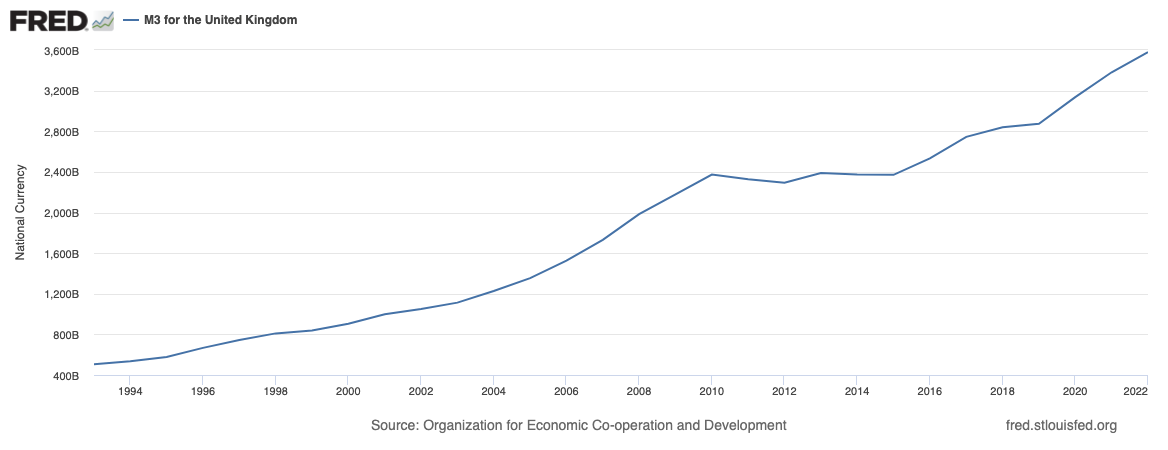

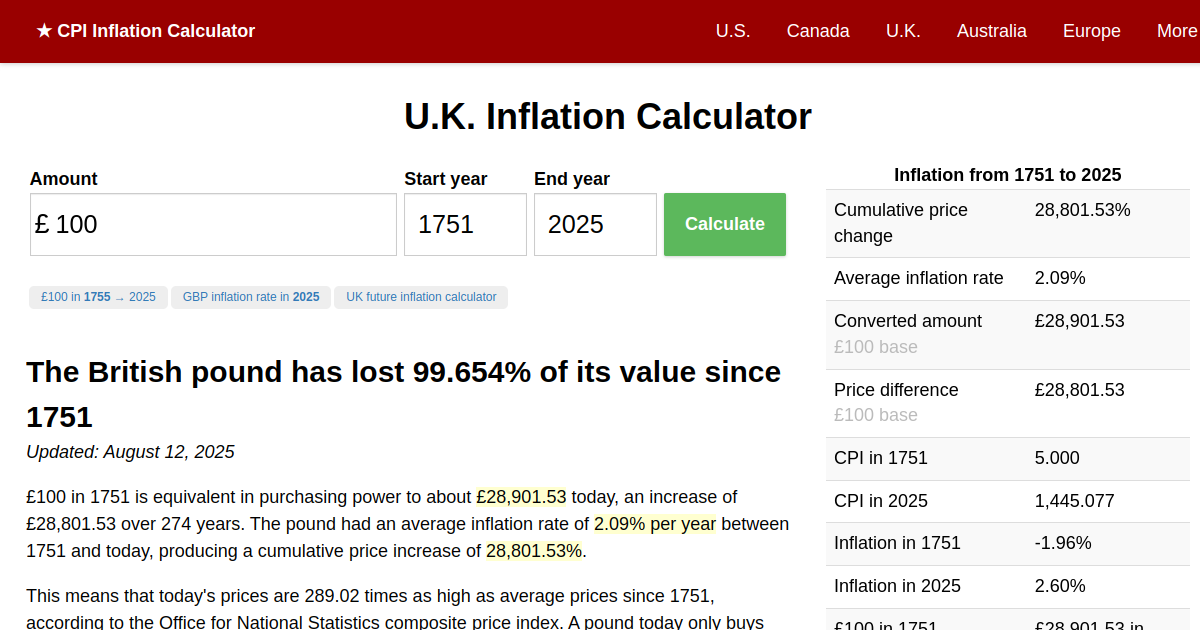

Broad money (M3) has increased sevenfold in a generation.

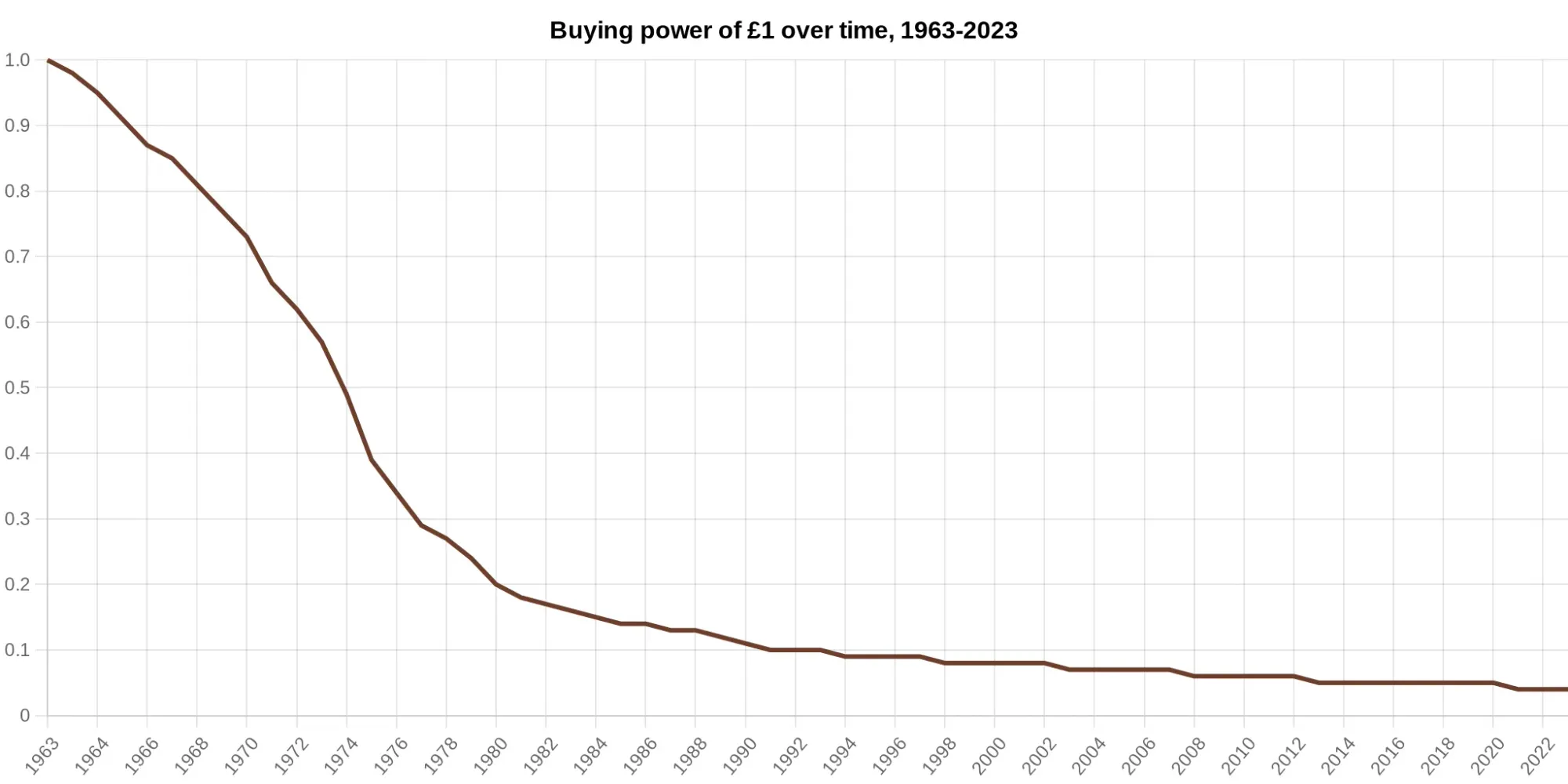

The pound has lost 62% of its purchasing power in a generation, 96% over two.

The mystery of inflation.

Inflation in our currency supply seems to filter through into the prices of goods and services in a rather unpredictable and disproportionate manner. Brits each have their own experience of this, but inflation ultimately becomes a problem no matter where you sit on the socioeconomic spectrum.

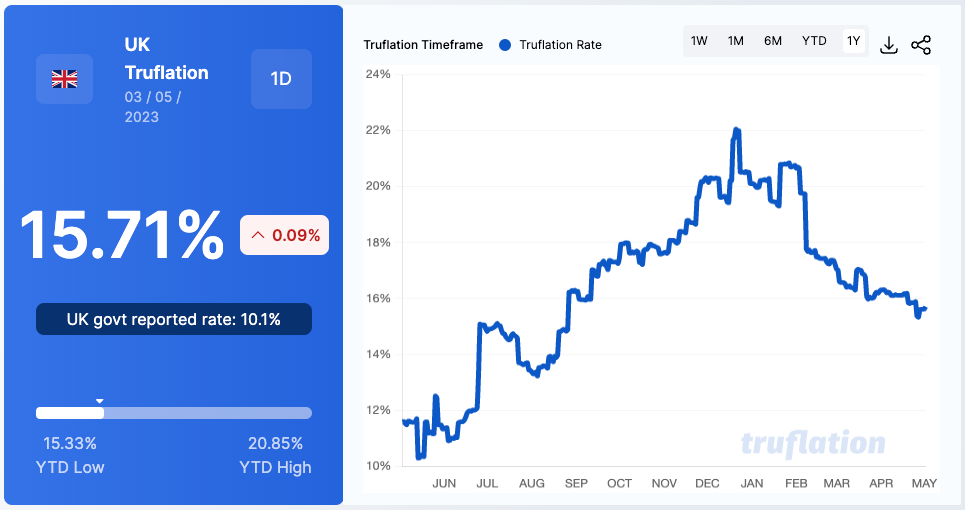

Following the global financial crisis in 2008, inflation in the UK primarily affected asset prices. However, in the aftermath of the response to COVID-19, inflation has spilled over into the prices of energy and groceries with a vengeance. In 2023 awareness of this is now acute. The mainstream media points the finger at greedy corporations raising their prices, or voices concern over the pay demands of striking workers. The Bank of England has suggested that people simply accept being poorer. It’s a pretty desperate situation.

If high inflation sticks around, maintaining a decent standard of living will remain a struggle for workers. In an attempt to outpace inflation, asset managers will be compelled to adopt increasingly risky investment strategies. Unfortunately, the simple connection between the expanding supply of the pound and its diminishing purchasing power often gets overlooked. That said, awareness of this connection is set to grow. It only takes a slight shift in perception to realise that prices are not merely rising; rather, the pound is losing its purchasing power as its supply expands. The failure of the pound as a reliable store of value will undoubtedly become a more prominent topic of discussion as the situation worsens. Our inflationary currency isn't fulfilling the functions of money, and the consequences are affecting everyone.

Inflationary currency meets the housing market.

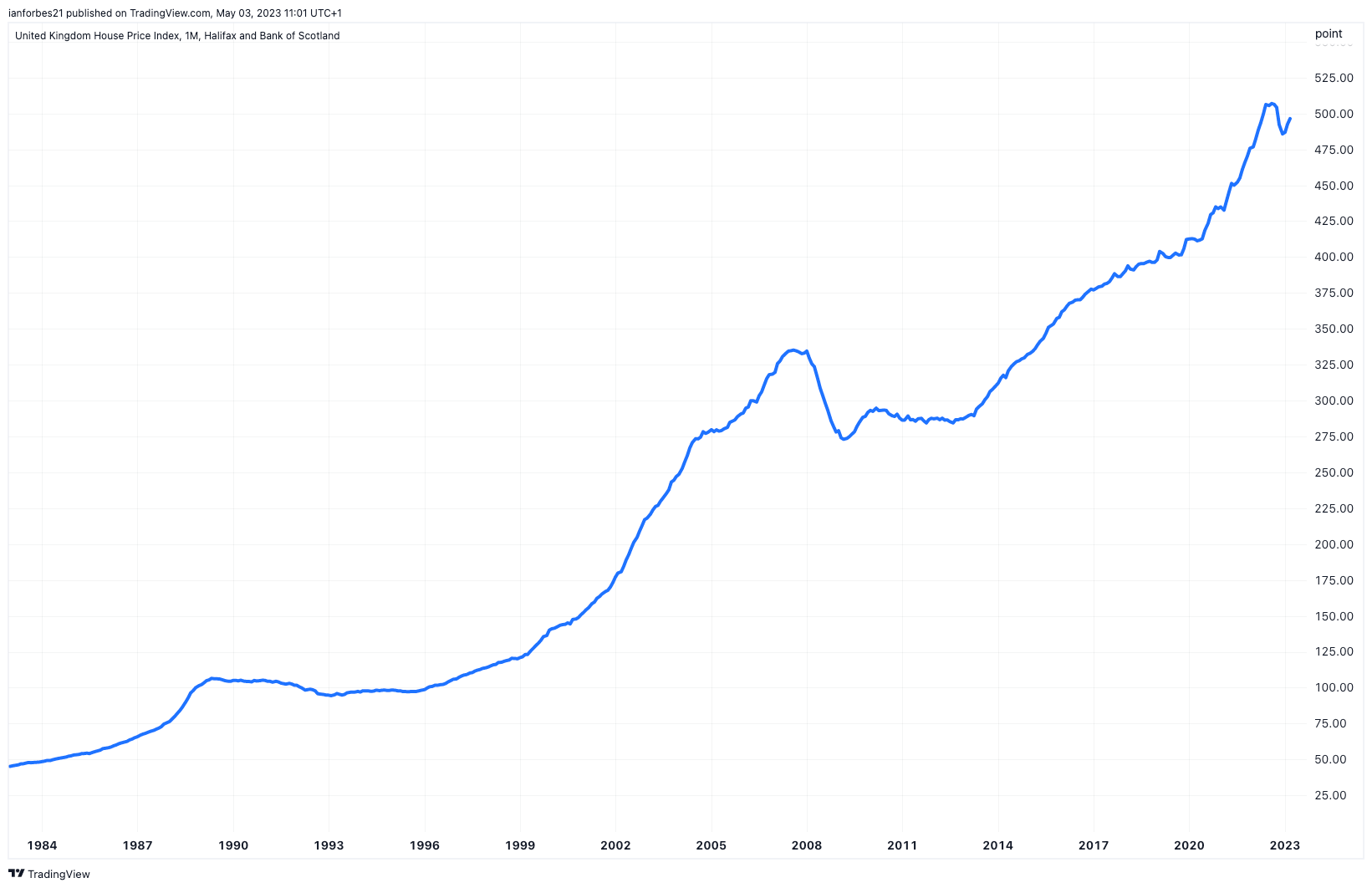

With the backdrop of a depreciating and inflationary currency, nominal house prices in the UK have reached unprecedented heights. The value of the pound relative to housing has plummeted. As a result, houses have become increasingly popular as not only a place to live but also a store of value. The allure of housing as a reliable investment option grew substantially through the 2010s, particularly in London and the South East of England.

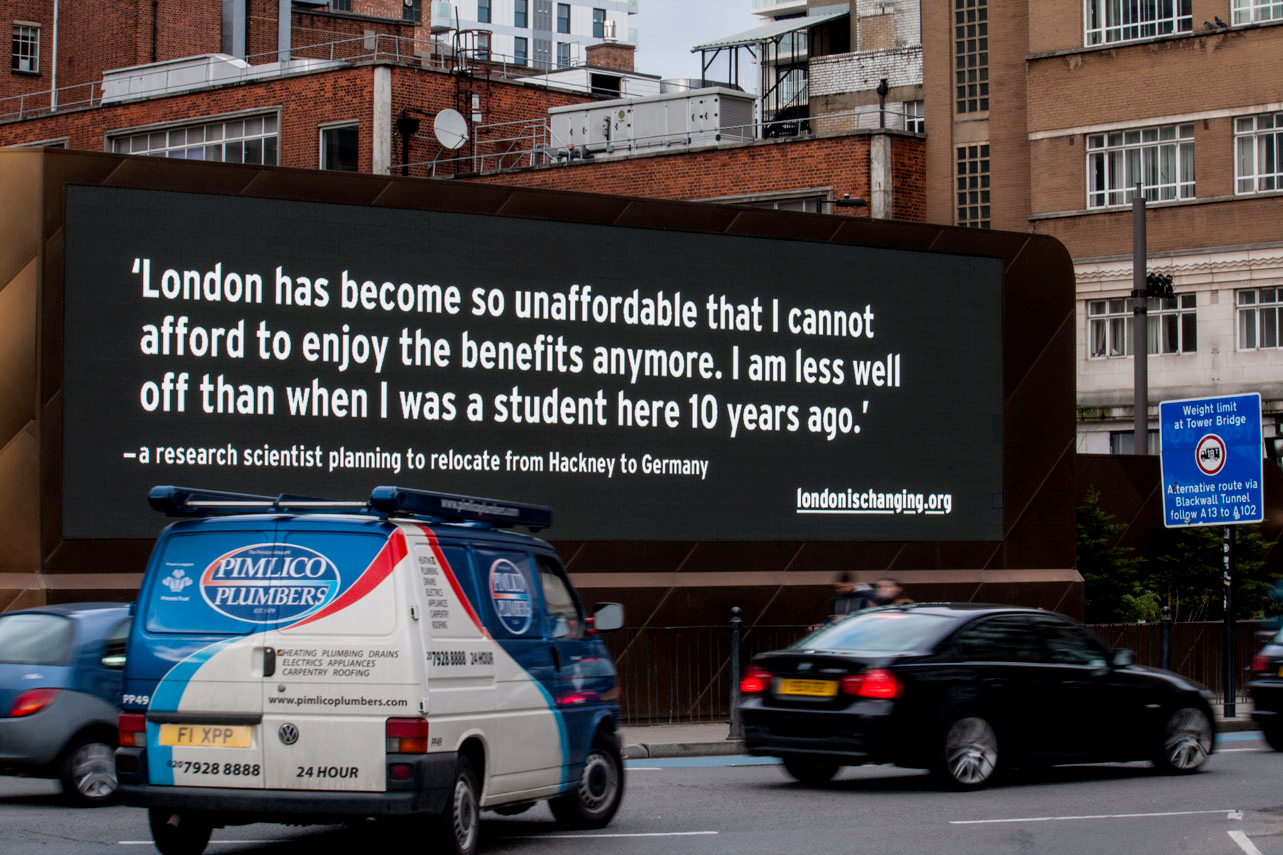

In London, scarcity in the housing market has reached a critical level. The interplay between the local and the global creates a complicated landscape, but demand seemingly knows no limits. Londoners who live and work on fixed salaries compete with deep-pocketed investors and speculators from around the world. Meanwhile, the supply of housing and available development land remains severely limited. In contrast to our ballooning currency supply, housing supply growth in recent years has been lackluster at best.

"Buy land, they're not making it anymore."

Mark Twain's often attributed quote, 'Buy land, they're not making it anymore,' resonates as a reminder of the perennial scarcity of land. That said, the recent period of unprecedentedly low interest rates has ushered in a wave of new capital flows, giving rise to mounting concerns about a housing bubble. Residential real estate developments have become vehicles to financialise, and even monetise land.

"Property is the world’s biggest store of wealth. Residential has pushed its value to new heights. The value of all the world’s real estate reached $326.5 trillion in 2020, a 5% increase on 2019 levels and a record high. Growth was driven by residential which is by far the largest real estate sector, accounting for 79% of all global real estate value. It saw its value increase by 8% over the year, to some $258.5 trillion."

Savills

The monetisation of land through residential real estate.

Circling back to the functions and properties of money, how do homes shape up as monetary goods?

The store of value function is the main attraction.

In contrast to inflationary currency, the allure of real estate lies in its role as a dependable store of value.

Scarcity; development land for new housing in the UK is in short supply, and there’s a shortfall of millions of homes in the market nationally. In London where scarcity is the most severe, companies are even working to develop the airspace above existing buildings.

Durability; less of a concern with land. While the structure of a modern apartment building boasts a lifespan spanning several generations, the maintenance and upkeep of its exterior facade and service systems require regular attention.

The medium of exchange function isn’t satisfied by real estate, but financialisation helps.

Acceptability; residential real estate is widely recognised as a form of collateral for loans and mortgages. Its status as a secure and stable asset allows property owners in one jurisdiction to leverage their holdings for financial purposes in another through cross-border lending.

Portability; buildings aren't portable, hence the mantra; “Location, location, location”. Global cities like London have become prime locations due to their relative market and political stability, developed infrastructure, and international appeal.

Real estate is an unlikely unit of account, but is increasingly optimised for the properties that support this monetary function.

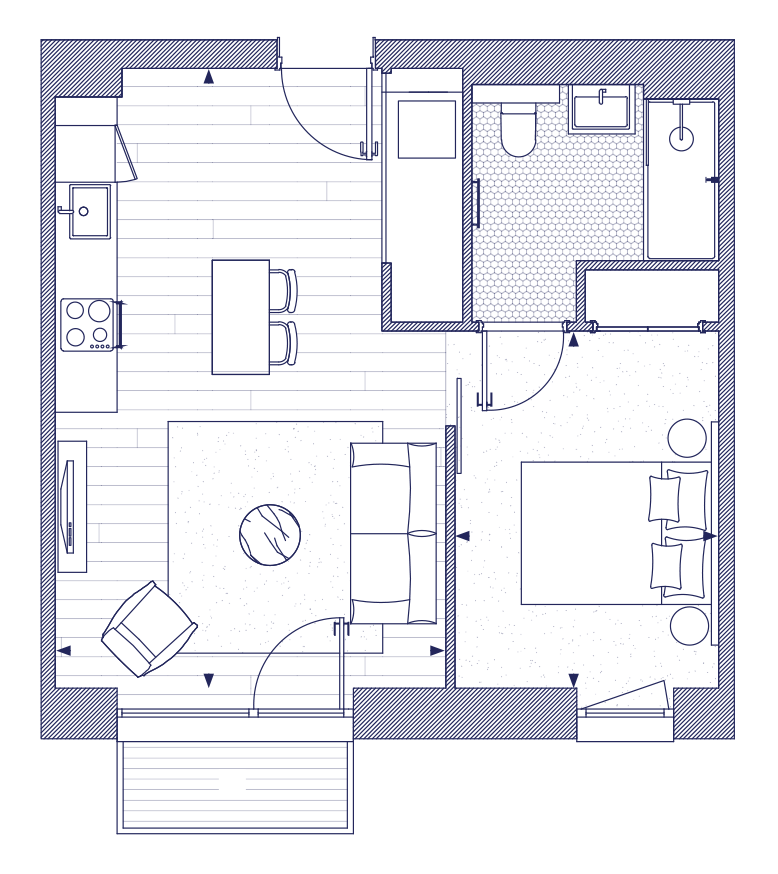

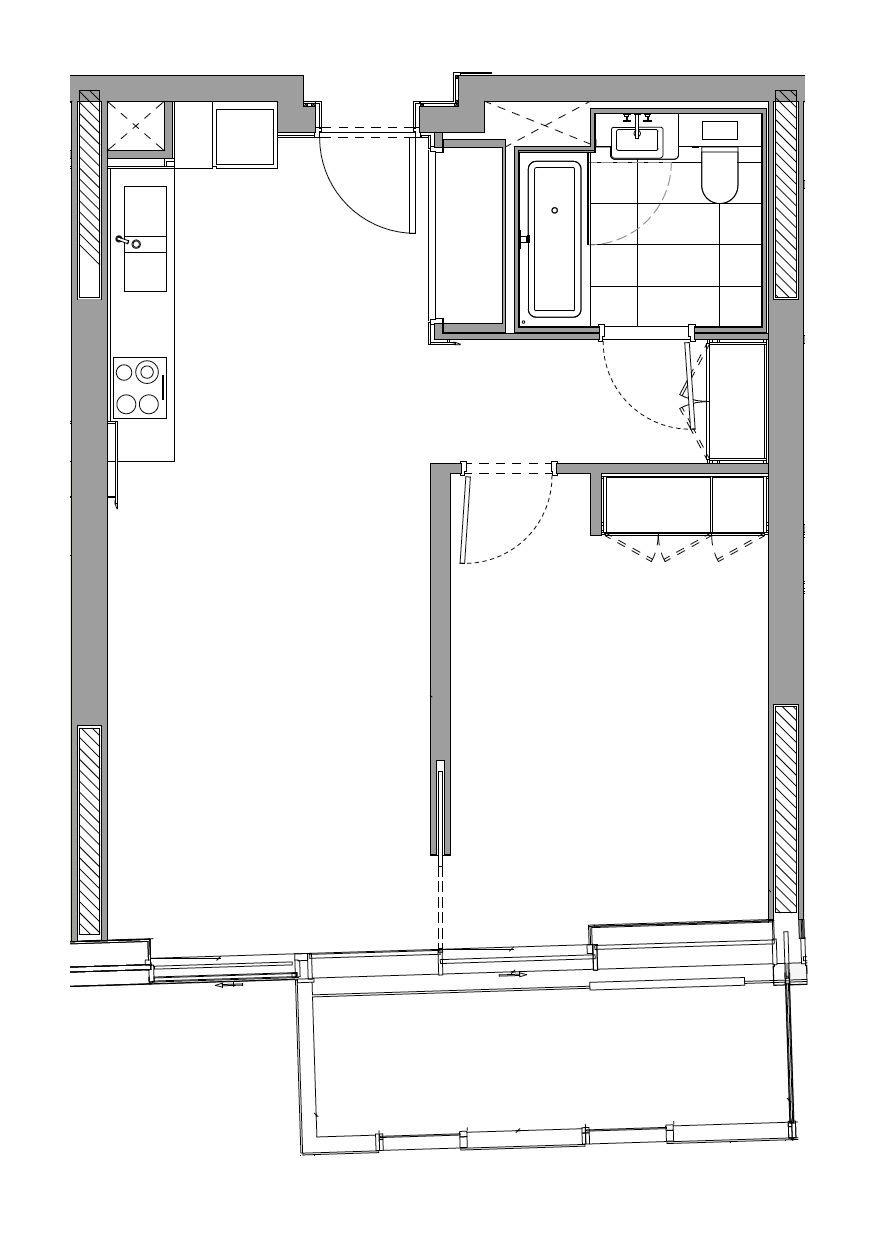

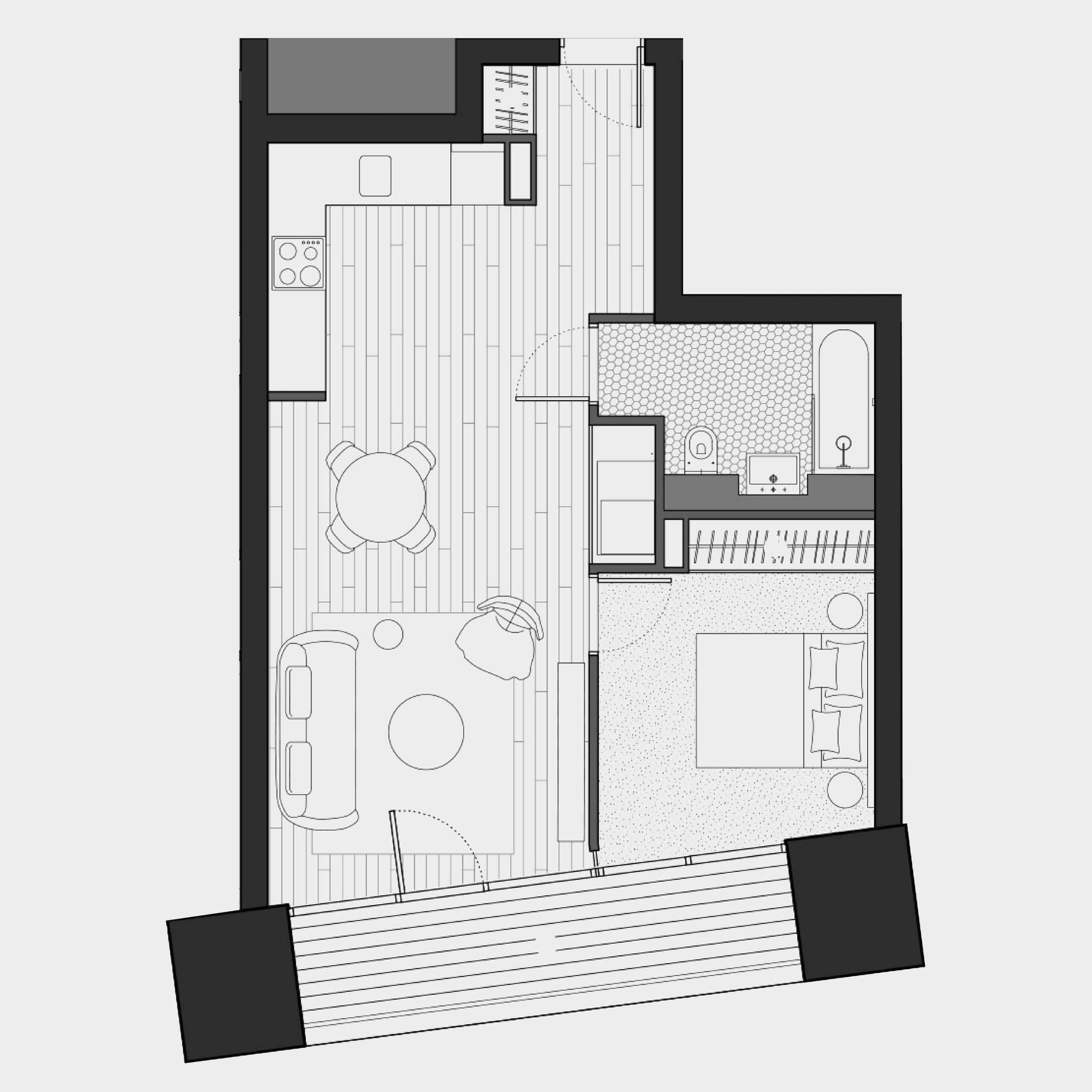

The divisibility of desirable land is improved through the development of residential real estate. Large sites can be divided into phases or blocks, providing more granularity by offering individual homes or "units" within each block.

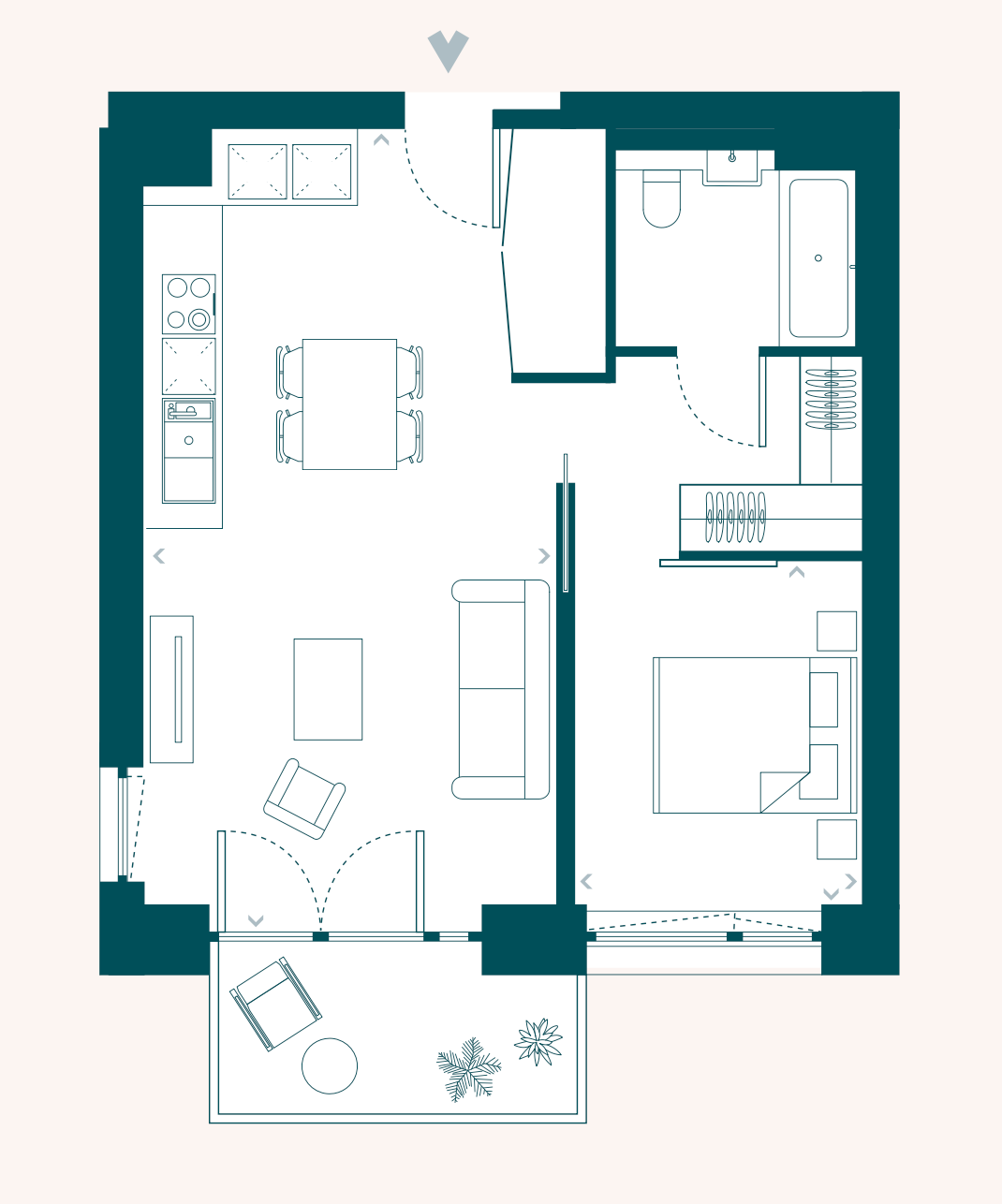

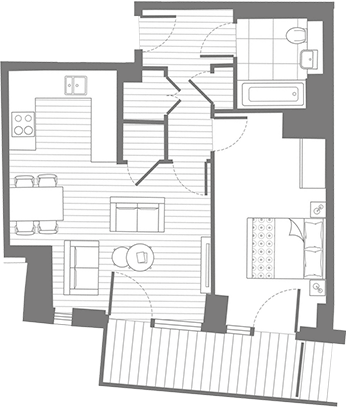

Fungibility is easy to spot in new-build residential real estate. While specific regulations, space standards, and market trends may influence the layout of individual units, tall buildings with repeating floor plans offer high levels of interchangeability. Units in different developments within the same city often bear close resemblances to one another, contributing to a perception of uniformity and ease of exchange.

Homes as money? Buy-to-leave as a smoking gun.

In the residential real estate market, it may seem strange to consider speculators purchasing houses as monetary goods for their store of value characteristics. Alongside owner-occupiers, you typically think of investors entering the market to purchase and lease out housing for rental income. A buy-to-let strategy looks for positive cash flows and capital appreciation. Easy money until something goes wrong with the property, interest rates, the tenants, or all three.

The phenomenon of buy-to-leave, however, sees residential property being bought to be intentionally and permanently left unoccupied. In London, the so-called platinum triangle between Knightsbridge, Mayfair and Belgravia has emerged as a notable hotspot for this trend. One prominent example is One Hyde Park, where the occupancy rate barely reaches 30 percent, with some apartments never having been lived in. In London more broadly, there are over 87,000 vacant properties, estimated to be worth in the region of £130 billion. While there may be other factors contributing to properties being left empty, speculation based on their performance as a store of value remains a significant driving force.

"When the dominant money becomes terminally ill, we witness the short-term monetisation of everything else"

Tuur Demeester

The prominence of the buy-to-leave trend in cities like London is a clear indication of a distortion in housing markets. This distortion largely stems from the underperformance of inflationary currency as a reliable store of value. Keeping the functions and properties of monetary goods in mind, it's evident that desirable residential real estate emerges as an attractive alternative for preserving wealth in the face of depreciating currency.

By intentionally leaving houses unoccupied, owners hope to easily sell or refinance them in the future, minimising maintenance costs and avoiding tenant-related complications. Not centred around traditional investment principles, buy-to-leave is a speculative trend fuelled by the devaluation of currency. Cash flows are rendered irrelevant when houses trade like monetary goods. Erik Yakes distinguishes between monetary value, and consumption (or utility) value in his study of monetary properties:

“The monetary value of a good is obtained by its ability to enable trade and is completely separate from the good’s market value for consumption.”

Erik Yakes

Buy-to-leave in London is a clear example of housing being purchased as a monetary good for future trade, rather than being bought for its utility as a place to live or as an investment with positive cash flows. With the UK’s housing crisis in mind, it’s staggering that homes are being designed and built only to be left empty and traded as monetary goods. Given the recent explosion in the supply of pounds and other fiat currencies, how many more homes will be captured by speculators and what are the knock on effects?

Consequences of buy-to-leave.

The demand for housing from Londoners seeking a place to live is strong, but it is arguably finite. In contrast, as currencies continue to inflate and lose their purchasing power, the global demand for a store of value is infinite. While some of this demand finds its way into the stock market or other alternative assets, residential real estate remains the most popular outlet and shows no signs of losing its top spot.

Although concentrated in specific locations, buy-to-leave puts upwards pressure on prices which ripple through the entire market. All types of demand are competing for the same limited number of homes. A majority of would-be owner-occupiers are collateral damage as a minority of wealthy speculators compete to pick up the nth property for their portfolio.

Buy-to-leave demand has created a positive feedback loop, contributing to a "monetary premium" in the housing market. The utility (or consumption) value of a home is relative to how it is perceived by locals or investors. The monetary premium reflects the extent to which prices inflate beyond this utility value. For a typical household, utility value may be based on their combined income and access to mortgage products. Buy-to-let investors, on the other hand, consider utility value in terms of mortgage rates and expected future cash flows. However, buy-to-leave speculators may disregard realistic salaries or mortgage deals, prioritising the exchange from currency—a poor store of value—into something scarce, with less sensitivity to price. They believe that nominal house prices only go up in the long term. Unfortunately, when a monetary premium arises in the market, everyone foots the bill.

The negative impacts of buy-to-leave extend beyond affordability. With limited space in cities, each house used by a buy-to-leave speculator means one less home available for an owner-occupier or tenant. The effects on urban life for genuine residents in neighbourhoods with numerous empty houses are significant. How safe do streets feel at night when so many of the lights are out? What use are absentee owners to local businesses like the corner shop? In managed apartment blocks, it can't be much fun for porters when natural levels of daily activity are missing due to buy-to-leave. Establishing a sense of a neighbourly community might be more challenging in some urban contexts, but if buildings are largely empty for some or all of the year, it's a non-starter.

The implications for the planning, design and construction stages of residential buildings are a further concern. The process leading up to a building being occupied (or not) is long and resource-intensive. If the raison d'être for a building project is creating a store of value rather than a place to live, the teams involved are getting a raw deal. How many architects have trained to design spaces that will never be occupied? How many contractors and tradesmen have perfected their craft only to erect lifeless buildings? Moving from one project stage to the next without the promise of any future residents is nothing short of demoralising for all parties involved. Buy-to-leave is an elephant in the room for professionals with an ethical code of conduct.

Addressing the issue.

As awareness of buy-to-leave grows, we can expect more debate and demands for a crackdown. Westminster City Council recently unveiled a plan which encourages residents to report empty homes through a new hotline. Reporting is a start, proposals which aim to reverse the trend are surely soon to follow. It’s easy to imagine various “stick” type approaches, such as introducing new taxes or penalties on the owners of homes which are left empty. These actions are likely to garner support from the majority of Londoners. After all, the store of value opportunity for the few is contributing to a housing crisis for the many.

We are launching a crackdown on empty homes in the city 🏠 📣

— Westminster City Council (@CityWestminster) March 7, 2023

Our measures will encourage owners to free up space for private rent and affordable homes, and discourage the purchase of holiday homes or ‘buy to leave investment’ 🏙️

Find out more 👇 https://t.co/OHriSIUdMK pic.twitter.com/ljOYHIR7xF

Addressing the housing crisis is a pressing political challenge, particularly in London, where the need for increased housing supply has become a top priority.

"The Mayor believes the only way to fix London’s housing crisis is to build far more new homes. These new homes need to be genuinely affordable to Londoners."

Mayor of London

Unfortunately, as long as our currency continues to underperform as money, the incentive to use houses as a store of value will persist. With tens of thousands of empty properties in London already, there's a concern that efforts to deliver new housing supply may be undermined. Speculators seeking a stable store of value may continue to choose London property, perpetuating the situation where houses remain vacant and unoccupied. However frustrating this dynamic might be, it's clearly a rational activity. Holding excessive amounts of cash isn’t an option, and housing remains an attractive alternative.

Considering the nature of inflationary currency, simply cracking down on vacant properties or increasing housing supply falls short of addressing the underlying incentives. A "carrot" approach should also be on the table for discussion. This might focus on establishing a superior monetary alternative to housing, particularly in terms of the store of value function. Whilst this could take the form of another asset class, ideally it should lead to the adoption of a more reliable currency that fulfils the three core functions of money.

“Abundance in money leads to scarcity everywhere else. Scarcity in money leads to abundance everywhere else.”

Jeff Booth

Closing thoughts.

The housing crisis in the UK continues unabated, despite the extensive attention it receives. There are already plenty of strong opinions on the causes and contributing factors, as well as potential solutions. Change the planning policy, build more homes, tax overseas investors, the list goes on. However, few have delved honestly into the role of our currency and its contribution to the market's dysfunction.

The arrival of Bitcoin has rekindled some fundamental questions about the nature of money. Bitcoin enthusiasts have tirelessly defended the merits of this new software network, although their arguments often fall on deaf ears. Nevertheless, they have succeeded in popularising the functions and properties of money, while exposing the shortcomings of cheap, inflationary currencies.

One of the critical functions of money is its ability to store value. When a currency is engineered to decay in value over time, individuals seek alternative ways to preserve their wealth. Residential real estate, with its relative scarcity compared to fiat currencies, has emerged as the favoured store of wealth globally.

"Property is the world’s biggest store of wealth. Residential has pushed its value to new heights"

Savills

Returning to the quote from Savills, keep in mind that using residential property as a monetary good captures its utility as a place to live (entirely so with buy-to-leave). What would the housing market look like if the world's favourite store of value was simply a better currency? Using a currency as a monetary good, there is no captured utility. It's difficult to envision speculators going through the trouble of acquiring multiple properties if they could merely hold onto their money and maintain stable purchasing power.

In a world with an expensive currency, one that scarce enough to serve as the best store of value, the disturbing phenomenon of buy-to-leave would disappear. The concept of buying houses as monetary goods to leave empty and trade up in future would become nonsensical. The monetary premium that has accumulated in the housing market would unravel, allowing houses to be used more efficiently as places to live or genuine investments.

If we truly desire a healthier housing market and a better built environment, perhaps we should prioritise the adoption of superior money as highly as the construction of more houses. The more houses that become real homes, the better!

References

How to critique Bitcoin: a guide, Nic Carter

This is Water, David Foster Wallace

The Dimensions of Money, Eric Yakes

Gold Sovereign coins, Coin Invest

Cash’s reign fades as Covid accelerates high street switch to card-only

M3 for the United Kingdom

U.K. Inflation Calculator

CPI Data by Truflation, UK

Halifax House Price Index

The total value of global real estate, Paul Tostevin

The housebuilding crisis: The UK’s 4 million missing homes

Rise Up, Skyroom

The impact of ‘buy to leave’ on prime London’s housing market, Financial Times

The UK Cities Worst Affected by the Housing Crisis, CIA Landlords

A Tale of Two Londons

More Money Supply, More Problems

Our vision for increasing housing supply and building homes for Londoners

Londoners will be encouraged to dob on their neighbours under new hotline plans

If the UK built 1 million homes, what would happen to house prices?

Bitcoin Has No Intrinsic Value — and That’s Great.

Empty housing in London, Michael Brooks

Why Houses Cost So Much - And What To Do About It